Environmental Concerns

Threatened and Endangered Species

AgSite reports include a list of threatened and endangered species that could inhabit the selected area. AgSite integrates data from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Environmental Conservation Online System to create the list, which may include both plant and animal species. For each species listed in the “Threatened and Endangered Species” table, users may click on the name to open a species profile. Within the profile, users can access information about a species’ listing status, recovery plans, petitions and other resources.

The AgSite table indicates the county where the species is considered endangered or threatened. A species listing in the table does not indicate that the species resides on the selected land in an AgSite report. It is merely a first indicator that the habitat for that species may exist in the selected area.

To qualify as an endangered species, the species must be recognized as nearly extinct throughout at least a significant part of its range. The extinction risk isn’t as imminent for threatened species; however, at some point in the foreseeable future, a threatened species will likely become endangered, according to the standard for being named a threatened species. Listing a species as threatened or endangered may originate from two different processes. In the first, any interested party may submit a petition requesting that the Secretary of the Interior add a species; a petition may also seek to remove a species from the list. In the second, called a candidate assessment, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service biologists recommend species candidates for listing.

In addition to federal protections for endangered species, states may add other measures. For example, Missouri has a Wildlife Code of Missouri that the Missouri Department of Conservation administers. The code includes all federally recognized threatened and endangered species and lists them as state-endangered. For other at-risk species in Missouri, the Missouri Department of Conservation may add those species to its state-endangered list.

Protections may differ for plants and animals. For example, the Missouri Department of Conservation specifies that landowners own threatened and endangered plants. They may choose to allow the plants to grow. Alternatively, they may destroy the plants, except in instances where federal funds are being used. Protections apply upon moving, selling, trading or transporting threatened or endangered plants. Animal species are considered public resources, even when on private land. Federal law prohibits killing or “taking” an endangered or threatened animal or harming its habitat; exceptions may be provided in some cases. State-level protections may vary. For example, in Missouri, state-endangered animals, not their habitats, are protected.

Sources and Other Resources:

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Endangered Species Act

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Financial Assistance

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Information for Planning and Consultation

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Environmental Quality Incentives Program

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Healthy Forests Reserve Program

Flood Hazards

AgSite reports share information about several parameters that can indicate flood hazards associated with a certain land tract. The flood hazards table presents the number of acres that fall within a floodway, 100-year floodplain and 500-year floodplain. It also shares any notes relevant to describing possible flood hazards.

The following definitions and discussion describe differences between a floodway and floodplain and their significance to landowners.

- Floodway: A floodway includes both a river or stream channel and the portion of a river or stream’s surrounding floodplain area that would play a role in efficiently managing that channel’s flood water or flood flow. Although the floodplain itself would normally contain dry, relatively flat land, water would cover the area during a flood.

- 100-year floodplain: In a 100-year floodplain, the area risks being flooded during a 100-year flood, which has a 1 percent probability of occurring annually. “Base flood” would be an alternate term for a 100-year flood.

- 500-year floodplain: In a 500-year floodplain, the area risks being flooded during a 500-year flood, which has a 0.2 percent probability of occurring annually.

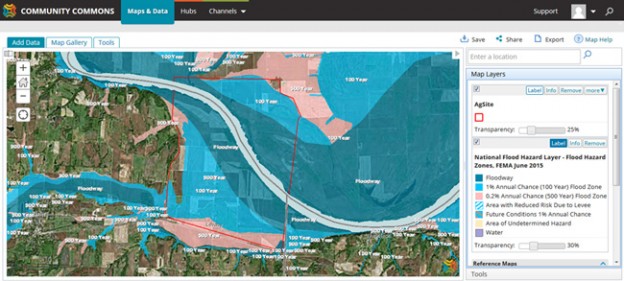

By clicking the “View map” link beside the “Flood Hazards” heading, users may load a map that shades the floodway, 100-year floodplain and 500-year floodplain areas that surround the selected site. The following map is a sample map that highlights the floodway, 100-year floodplain and 500-year floodplain areas. From the “Map Layers” window, users may modify the flood hazards map by selecting to add or remove various reference map features, such as highways, place names and topographic features.

From the map view’s “Tools” window, AgSite users may query the flood hazard data set as they search by flood zone code, flood zone subtype, mapping designation or special flood hazard area. After running a query that returns results, click “Show Attribute Table” to display search records that fit the query criteria. For example, a user may search for a specific special flood hazard area, which represents an area that a base flood would cover with floodwaters, an area subject to National Flood Insurance Program floodplain management regulations and an area requiring a flood insurance purchase. On the map itself, an AgSite user may click an area highlighted as a floodway or floodplain to open that area’s data profile.

Floodplain areas pose certain risks and possible rewards for landowners. For example, if a landowner builds a home within the floodplain, then that home would be more likely to experience damage during a flood and need additional insurance coverage relative to homes built on higher ground. From an agricultural perspective, however, the fertility found in floodplains makes these areas well-suited for farming. Flood waters move nutrient-rich sediment into a floodplain that can support crop growth, and a floodplain’s physical properties – relatively flat and containing few obstacles – would also support its potential for agricultural production. Floodplains also contribute to aquifers and create a habitat for wildlife populations.

Floodplains and the surrounding land are subject to the Clean Water Act. Neighboring water is a term used to describe water not actually considered a stream and subject to the Clean Water Act. Neighboring waters have at least part of their area situated within the 100-year floodplain and within 1,500 feet of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, territorial sea, impoundment or tributary’s ordinary high water mark. Persons with floodplains on their land may need to seek a permit to make management changes to land within 1,500 feet of the edge of a floodplain.

Sources and Other Resources:

- Federal Emergency Management Agency, Special Flood Hazard Area

- Harris County Flood Warning System, Glossary of Terms

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) Program

- USGS, Water Science Glossary of Terms

Sinkhole Susceptibility

A sinkhole is a depression in the ground that has no natural external surface drainage. Basically, this means that when it rains, all of the water stays inside the sinkhole and typically drains into the subsurface.

Sinkholes are most common in what geologists call, “karst terrain.” These are regions where the types of rock below the land surface can naturally be dissolved by groundwater circulating through them. Soluble rocks include salt beds and domes, gypsum, limestone and other carbonate rock.

When water from rainfall moves down through the soil, these types of rock begin to dissolve. This creates underground spaces and caverns.

Sinkholes are dramatic because the land usually stays intact for a period of time until the underground spaces get too big. If there is not enough support for the land above the spaces, then a sudden collapse of the land surface can occur.

Within an AgSite report, landowners can determine whether a given property has any sinkhole susceptibility. The USGS Sinkhole Susceptibility Index identifies potential sinkhole hotspots based on current conditions and underlying geology. Areas characterized as having either high or very high sinkhole susceptibility contain 94-99% of known or probable sinkhole locations from three U.S. state databases.

To avoid potential environmental concerns, such as water contamination, landowners may adopt several management practices. For example, establishing a vegetative buffer – made from grass, bushes and trees – that surrounds a sinkhole would enable the vegetative matter to filter contaminants from surface water runoff. The vegetative matter’s roots would also stabilize the sinkhole’s walls, and the buffer may reduce equipment wear as it removes the sinkhole’s surrounding area from agricultural production. Other sinkhole stabilization efforts could involve excavating the sinkhole to the bedrock and filling it with rock. Installing a fence 25 feet from the sinkhole’s depression rim would exclude livestock from the area. By prohibiting livestock from being near sinkholes, landowners limit manure, sediment and pollutant runoff from reaching the sinkhole, and they avoid their livestock being injured by the sinkhole.

Sources and Other Resources:

- Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Karst in Missouri

- University of Kentucky, Sinkhole Management for Agricultural Producers

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Environmental Quality Incentives Program

- Karst Waters Institute